top of page

Donna Esposito

Longer and Longer Shadows:

My Search for Missing Marine PFC Haig Sarafian

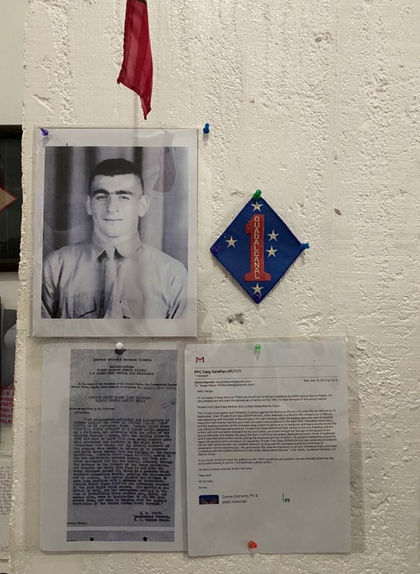

PFC Haig Sarafian, USMC Photo

Haig Sarafian was born on 23 September 1925 to Puzant Sarafian and Elizabeth Kistorian Sarafian in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Haig’s parents were Armenian immigrants from Turkey who had escaped the Armenian genocide. Puzant had arrived in the United States in 1916. Elizabeth arrived in 1921 to marry Puzant; she was just 17 years old.

By 1930, Puzant was a wallpaper hanger and Elizabeth was employed as a picker in a silk mill. Haig was an only child. At some point in the 1930s, Elizabeth left Puzant. By 1940 Haig was no longer living in Philadelphia with either parent, but was an “inmate” at the Luzerne County Industrial School for Boys in Butler Township, just outside of Hazleton, about 100 miles north of Philadelphia in the Coal Region of Pennsylvania. Known locally as “Kis-Lyn,” the school was founded to rehabilitate nonviolent juvenile offenders and provide a home for boys with unstable living arrangements. It’s unclear why Haig was attending this school, but it was clear he did not want to stay there: Haig, along with several other boys, escaped from the school in October of 1940 and again in January of 1941. At some point that year, he was able to return to Philadelphia to attend Overbrook High School. However, Haig did not graduate. With his mother’s permission, he enlisted in the US Marine Corps in Philadelphia on 12 January 1943 at the age of 17.

After completing boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, Haig received additional training and departed from San Diego aboard the S.S. Lurline on 18 April 1943. After stays in American Samoa, New Caledonia, and New Zealand, Haig was ultimately assigned to the Third Defense Battalion as part of the Special Weapons Group. He arrived on Guadalcanal, no longer on the front lines, on 5 October 1943. After participating in amphibious landing exercises, Haig departed Guadalcanal on 30 October 1943 for the invasion of Bougainville in the Northern Solomons. The Third Defense Battalion came ashore on D-Day, 1 November 1943, at Cape Torokina after the first waves of troops and had their heavy machine guns and light antiaircraft guns in place by that evening to defend the new beachhead. They continued their defense until 1 February 1944 and then moved to defend the airstrip at Torokina. The Third Defense Battalion remained on Bougainville for longer than any other unit. They finally departed on 12 June 1944 and returned to Guadalcanal.

The Third Defense Battalion was destined to remain on Guadalcanal, now very far from the fighting, until the end of December 1944 when it was ultimately disbanded. However, despite the many opportunities for recreation now available on the island, boredom must have set in. PFC Haig Sarafian repeated his escape trick from Kis-Lyn and went AWOL.

When Marines of the 1st Division arrived for practice landings prior to their next invasion, Haig and his friend Pvt. Charles W. Wartell of Chicago, Illinois, stowed away aboard a troopship heading to the battle. They boarded the attack transport U.S.S. Warren (APA-53) on 6 September 1944 at Tetere on Guadalcanal. The ship got underway on 8 September for their destination: Peleliu in the Palau Group of the Caroline Islands. On the 11th, now safely en route with no means to return to Guadalcanal, Haig and Charles came out of hiding or were discovered. They were assigned to Company C of the 1st Battalion of the 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division (C-1-1).

Administrative Ledger Of 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, 1st First Marine Division

11 Sept 1944-14 Sept 1944

Under the command of Capt. Everett P. Pope, Haig and Charles landed at White Beach 2 on D-Day, 15 September 1944. Although the resistance was much more fierce than what they experienced at Bougainville, both men made it safely ashore. Peleliu was expected to be a 2 to 3 day battle. Fighting their way off the beach and toward the coral ridges dotted with caves, pillboxes, and gun emplacements, it soon became clear it was going to be a much longer fight as heavy casualties mounted quickly.

By the morning of the 5th day on Peleliu, 19 September 1944, C Company was reduced to just 90 men from its initial strength of 235. Haig and Charles were still among them. The remains of C-1-1 were given the task of crossing a swamp to attack a high coral ridge called Hill 100. By then end of the day, Hill 100 was occupied by what was left of the company. Haig and Charles were not there, however. A small group of men under the command of Capt. Pope spent a harrowing night trying to hold the ridge, which they soon realized was a plateau; the Japanese were firing on them from three sides. Their ammunition depleted, they resorted to throwing rocks to mimic grenades and engaged in hand-to-hand combat throughout the night. In the morning, they were permitted to retreat. C-1-1 now consisted of about a dozen men. For this action, Capt. Pope was awarded the Medal of Honor.

At some point during the assault on Hill 100 on the 19th, both Haig and Charles were wounded. Charles suffered a blast concussion and was evacuated to the U.S.S. Leedstown for medical treatment. He was returned to duty the next day and managed to survive for the next few days until the depleted unit was evacuated. Haig, however, was seriously wounded after attacking an enemy pillbox and putting it out of action with a grenade. Capt. Pope believed Haig was evacuated to one of the ships treating the wounded and nominated him for a Silver Star for his gallantry. He also wrote to Haig’s commanding officer asking that he be transferred to C-1-1 and not punished for going AWOL.

Posthumous Silver Star Citation for PFC Haig Sarafian

However, the Marine Corps lost track of Haig Sarafian. He was not recorded as a casualty or recorded as being treated on any ship. He was not even added to the C-1-1 muster rolls to account for his time while AWOL. While the chaos of the battle can explain some of the lapses in recordkeeping, another factor was that Haig had lost (or discarded) at least one of his dog tags on Guadalcanal. So Haig’s family was not notified that he was a casualty. It was not until January 1945 when Haig’s mother began writing to the Marine Corps because she had not heard from her son since August 1944 that they even suspected he was missing. Initially they dismissed Elizabeth’s concerns, telling her they would tell him to write home. It was only later that they began to search the records for him and realized he was missing.

Eventually, in September 1945, the month the war ended, the Marine Corps finally admitted to Elizabeth that her son was missing in action and they didn’t know what had happened to him. He was officially declared dead on 22 January 1946. PFC Haig Sarafian’s Silver Star citation was updated to be a posthumous award. Haig’s parents could never have known what happened to him since the Marine Corps didn’t even know.

Haig’s mother eventually remarried and left Philadelphia for Worcester, Massachusetts. She erected a memorial marker for her son at the Massachusetts National Cemetery. PFC Haig Sarafian is also memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines.

Haig’s story only came to light because a local man found his lost dog tag in the Tetere area of Guadalcanal. Hoping to return the tag to a relative, I was astonished to uncover his tragic story. I have not been able to locate a living relative and the tag remains with the family who found it. They have chosen to honor its original owner by naming their son Haig.

Despite having no relatives to remember him, or perhaps because of this, I made it my mission to attempt to find out what happened to Haig and how he was lost. While his remains could still be missing on the island of Peleliu or they could have been buried as an unknown, the fact that people from C-1-1 believed Haig was evacuated and made the effort to request he be allowed to join their company suggests to me he was indeed evacuated. All casualties were being treated aboard ships at that point. The most plausible explanation for Haig’s fate was that he was evacuated alive, though probably unconscious, to a ship where he later died and was buried at sea as an unknown. He would not have been with people who knew him and he was missing at least one dog tag. Indeed, two people who were wounded on 19 September 1944 died aboard the U.S.S. Crescent City on 21 September 1944 and were buried at sea as unknowns. Other C-1-1 casualties were treated aboard the ship that same day, so it is possible that PFC Haig Sarafian was one of those two unknowns or an unknown buried at sea on another ship.

Although we will probably never know exactly what happened to Haig Sarafian, he will not be forgotten. In September 2019, I travelled to Peleliu for the 75th anniversary of the battle. It was an honor to stand on White Beach where Haig and so many others came ashore under heavy fire and tell his story. It was an incredibly special experience to climb to the top of Hill 100, now peaceful and covered in lush vegetation, and pay tribute to PFC Haig Sarafian, Pvt. Charles Wartell, Capt. Everett Pope, and all the men of C-1-1, many of whom made the ultimate sacrifice 75 years before.

Acknowledgements: A very special thanks to Bill Francis, Anderson Giles, Tim Gray, the late Tangie Hesus, Anthony Hewitt, David McQuillen, the late Ambassador Laurence Pope, and Tomomi Takemoto.

For references and more documents and photos, please see the memorial for Haig Sarafian on Fold3.

Want to get involved and honor the fallen of WWII? Check out the Stories Behind the Stars project!

bottom of page